|

|

|

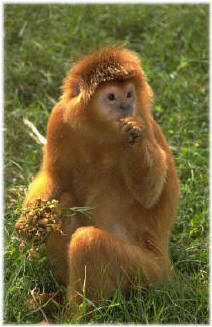

Animals in Captivity vs.

Animals in the Wild

Kah Ying Choo

One of the key problems with placing animals in captivity is the fact that the typical development of their authentic being is arrested at all levels. Although scientists working with animals in captivity claim that the needs of these creatures are satisfied, they have failed to acknowledge the adverse impact of the deficiencies of the physical and social environment on the quality of life of these animals.

For example, orcas and dolphins in the wild exhibit high intelligence, a strong need for social interaction and intense activity. The challenging environment in the ocean propels them to exercise their physical and mental |  |  | prowess constantly. In contrast, the typical physical and mental activity of dolphins in aquariums is limited by the static quality of the environment and the size of the tanks. Essentially, the orcas and dolphins are living in prisons (Animal Protection Institute, 2000, p. 1).

Another negative side-effect associated with the physical environment provided to dolphins in captivity has been found in the study of echolocation in captivity. Unlike the ocean that has softer sounds covering a wider bandwidth, dolphins in captivity often become deaf when they are exposed to the excessive concentration of sounds in the aquariums. Concomitantly, their ability to function normally is also affected (Ellis, 1982; Harrison et al., 1994).

Moreover, animals in the wild such as dolphins and orcas co-exist in distinctive groups and forge strong and enduring bonds with one another, which can last for as long as ten years. Within each of these groups, or pods, the family members communicate with one another with their own unique vocalizations. On the other hand, in captivity, the development of social organizations among the dolphins is undermined by the fact that family members can be traded and sold to other aquariums. Some dolphins are separated from their mothers when they are only six months old, thus preventing them from experiencing a typical social life (Animal Protection Institute, 2000, p. 1). In addition, different species of dolphins that have different social organizations and habits are restricted to the choice of their tank mates without the possibility of seeking out members of their own species.

Without the opportunity to learn social organizations and habits, many animals in captivity are unable to nurture or care for the young. In the case of chimpanzees, wild female chimps acquire their nurturing skills from their mothers and other female relatives within their social group. However, young chimps that have grown up in captivity do not have the opportunities to learn from their wild-born relatives. More adapted to human ways, these female chimps have lost their natural propensity and skills to care for their own young (Rock, 1995, p. 71). | |  | | Therefore, animals in captivity are affected by extreme boredom, lack of appropriate exercise, poor quality food and a lack of variety of food, especially in poorly run facilities. Since the development of their natural instincts and typical behavior has been stifled prematurely, animals in captivity that are released are unable to function normally in the wild. Animals in captivity that are used to being fed with dead fish and meat by trainers are unable to eat live fish.

Unaware of the social organization that exist in the wild, dolphins and orcas that attempt to join pods of animals of a different species are often attacked. In fact, the mortality rate of the released captive animals is 15 percent (Ellis, 1982; Harrison et al., 1994). While this fact can be used to support the captivity of animals, it | testifies to the tragedy of animals in captivity, which have lost their connection to their authentic being and identity at every level.

Because they are deprived of their natural environment, social interaction and typical activity, animals in captivity often divert their energies and anxiety into stereotypical behavior that are not evident in animals in the wild (Animal Protection Institute, 2000, p. 2). For example, tigers in the wild typically spend ten hours of the day hunting and monitoring their territory. However, their circus counterparts that are unable to perform these activities are forced to replace the typical physical activity by pacing their cages in order to release their energy. In their study, Nevill and Friend discovered that only by providing circus tigers with opportunities for exercise did the amount of pacing decrease (cited in Chenault, 2002, p. 2). The above discussion has illuminated the tragic consequences of suppressing the typical development of animals by placing them in captivity. Deprived of their natural environment and social groupings, these creatures are unable to learn in a way that will help them achieve their full potential and realize their authentic being. Instead, their natural activity is transformed into stereotypical behavior such as the tigers’ pacing of their cages or unpredictable eruptions of aggression by circus elephants. I believe these concepts can be extrapolated to young school children who are trapped not only within the physical confines of the school classroom, but also its oppressive rules and expectations, thus preventing them from achieving their human potential.

References

Animal Protection Institute (2000, April). Serving a life sentence: orcas and dolphins in captivity. Retrieved August 19, 2002, from http://www.api4animals.org/doc.asp?ID=300&print=y

Chenault, E. A. (2002, July 2). Hold that tiger: research studies circus tigers’ behavior, environment. AgNews. Retrieved August 19, 2002, from http://agnews.tamu.edu/dailynews/stories/ANSC/Jul0202a.htm

Ellis, R. (1982). Dolphins and porpoises. New York: Alfred & Knopf, Inc.

Harrison, R., et al. (1994). Whales, dolphins and porpoises. New York: Facts on File, Inc.

Rock, M. (1995, March). Human ‘moms’ teach chimps it’s all in the family. Smithsonian, 25(12), 70-75. PRINTABLE PAGE | BACK | TOP | NEXT | PRINTABLE SITE | | |